Definition

Bacillary dysentery is an acute invasive enteric infection caused by bacteria belonging to the genus Shigella. It is clinically manifested by diarrhea that is frequently bloody. In addition, it is an infection disease that causes intestinal inflammation that leads to the formation of micro-ulcers and inflammatory exudates, and causes inflammatory cells (polymorphonuclear leukocytes, PMNs) and blood to appear in the stool which can range from minor to severe and can be life-threatening to the patient

The infection is also called shigellosis, bloody flux and Marlow Syndrome.

Morphological Description

The causative agent, Shigella, is a small, gram-negative, straight rod, non-motile, non-lactose fermenting, facultative and anaerobic and coliform bacillus. Moreover, it possesses a capsule non-spore forming rod-shaped bacterium closely related to Eschericia coli and Salmonella. In addition, the rod-shaped bacterium contains K antigen and O antigen wherein the K antigen is not useful in serologic typing, but can interfere with O antigen determination. In addition, it belongs to the family Enterobacteriacae. There are for Shigella species, all of which causes bacillary dysentery: Shigella dysenteriae, Shigella flexneri, Shigella boydii and Shigella sonnei (also known as Groups A, B, C, D respectively)

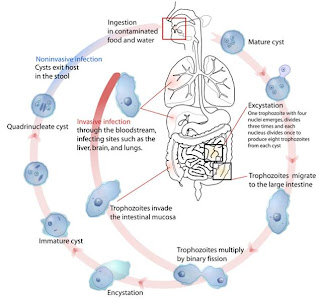

Mode of Transmission

The bacterium is spread by direct contact with an infected person. Transmission by fecal-oral route occurs via fecally contaminated water and hand-to-hand contact.

Signs and Symptoms

Bacillary dysentery signs and symptoms include diarrhea with or without the release of blood, tenesmus, and mild to very high fever, rectal pain, abdominal cramps and nausea and vomiting. These acute bacillary symptoms may last for a week or even for months. However, chronic bacillary dysentery may even cause some severe and fatal diseases such as hemolytic uremic syndrome. Chronic bacillary dysentery in children especially in malnourished children may unfortunately lead to the influx of bacteria into the bloodstream. Other symptoms may be intermittent and may include recurring low fevers, abdominal cramps, increased gas, and milder and firmer diarrhea. One may feel weak and anemic, or lose weight over a prolonged period (emaciation).

Diagnostics and Laboratory Tests

The different diagnostic and laboratory tests in determination of the infection are the following:

1. Examination of the stool sample.

2. Confirmatory tests

3. Serological identification for the presence of Shigella.

4. Sensitivity tests

Furthermore, there are series of specific tests to determine the presence of the bacterium.

1. Specimens from fresh stool, mucus flecks and rectal swab for culture

2. Culture.

| Serotype | Mannitol | Lactose | Glucose | ONPG | Tartrate Utilization |

| A | - | - | + | V | + |

| B | + | - | + | - | - |

| C | + | - | + | V | - |

| D | + | -/+ | + | + | + |

*v – variable 10-89% of strains are positive

· EMB/ MacConkey – positive visible result of colorless colonies

· SSA – colorless colonies without black center

· HEA – green colonies without black center

· TSI – acid butt, alkaline slant, no gas and H2S

· MR – positive result

· Citrate test, ODC test, ADH test, Deaminase and Urease test – negative result

· Sucrose, salicin and adonitol and dulcitol – negative result

· D-mannose – positive visible result in CHO fermentation

Period of Communicability

The infection is communicable for 1-7 days with an average of 4 days as long as the infected person excretes Shigella in stool.

Incubation Period

1-4 days but may be as long as 8 days.

Prognosis

The disease is self-limiting, has mild infections usually subside within 10 days. Severe infections, however, may persist for 2-6 weeks. Most cases of the infection subside within 10 days with correct treatment. Most individuals will achieve a full recovery within 2-4 weeks after beginning proper treatment. If the disease is left untreated, the prognosis varies with the immune status of the individual and the severity of the disease. The person can be a carrier of the infection for up to four weeks but usually less.

Prevention and Treatment

Antibiotics usually used in treating Shigellosis are the following:

1. Fluoroquinones (DOC)

2. TMP – SMX (trimethorpin-sulfamethoxazole)

3. Azithromycin

Some supportive measures can prevent the disease, such as proper hand-washing, drinking safe water, breastfeeding infants and safe handling and processing of food.